Unraveling Sons of Welder’s Magnus Game Series

"There was no intention when I created [the animations]. They were created years ago and were a pure manifestation of creativity without any idea. I came back to them after many years and understood that they are about a descent into darkness, being locked into patterns, transformation, change and rebirth, just like the entire Magnus Imago game. It's all connected all the time. I had to become mature myself to understand something that I once created."

Seeking meaning through creativity is, I suspect, something a lot of us try and do. It's the reason I started writing about games in the first place, almost a decade ago now. Especially when our 9-to-5's feel like we're just another cog in a machine - who's output has no bearing on our level of success or failure in life - the innate impulse to put something out into the world, something that bears our own inherently unique mark, fills us with a sense of accomplishment that decades of grinding away for corporations can never replicate. It's a form of "work" that is fundamentally different to the excesses and extractions of wealth our world is built around; this work promotes internal growth, self determination and freedom, in ways our heavily structured and overburdened professional lives can not fundamentally comprehend.

Speaking with Przemysław Geremek, one half of the Sons of Welder duo behind the now complete quadrilogy of Magnus games, I get the sense the creations these two brothers have spent the past couple of years working on sit at the heart of this journey for them. The four games - Magnus Failure, Magnus Imago, Magnus Positive Phototaxis and Lazarus A.D. 2222 - might only be about an hour in length each, but at the heart of all of them is a drive to crack open the shell of our current existences, and to explore a new world and a new self in the process. To escape the confines we find ourselves in, to stop thinking about what is, and start thinking about would could be.

Magnus Failure

Magnus Failure is the clear starting point, with an isometric representation of your character a grounding point to become invested in. Beginning in a disheveled shack before venturing into the surrounds, a point and click adventure game structure has you collecting a backpack full of increasingly esoteric items in order to open a path up for future adventures.

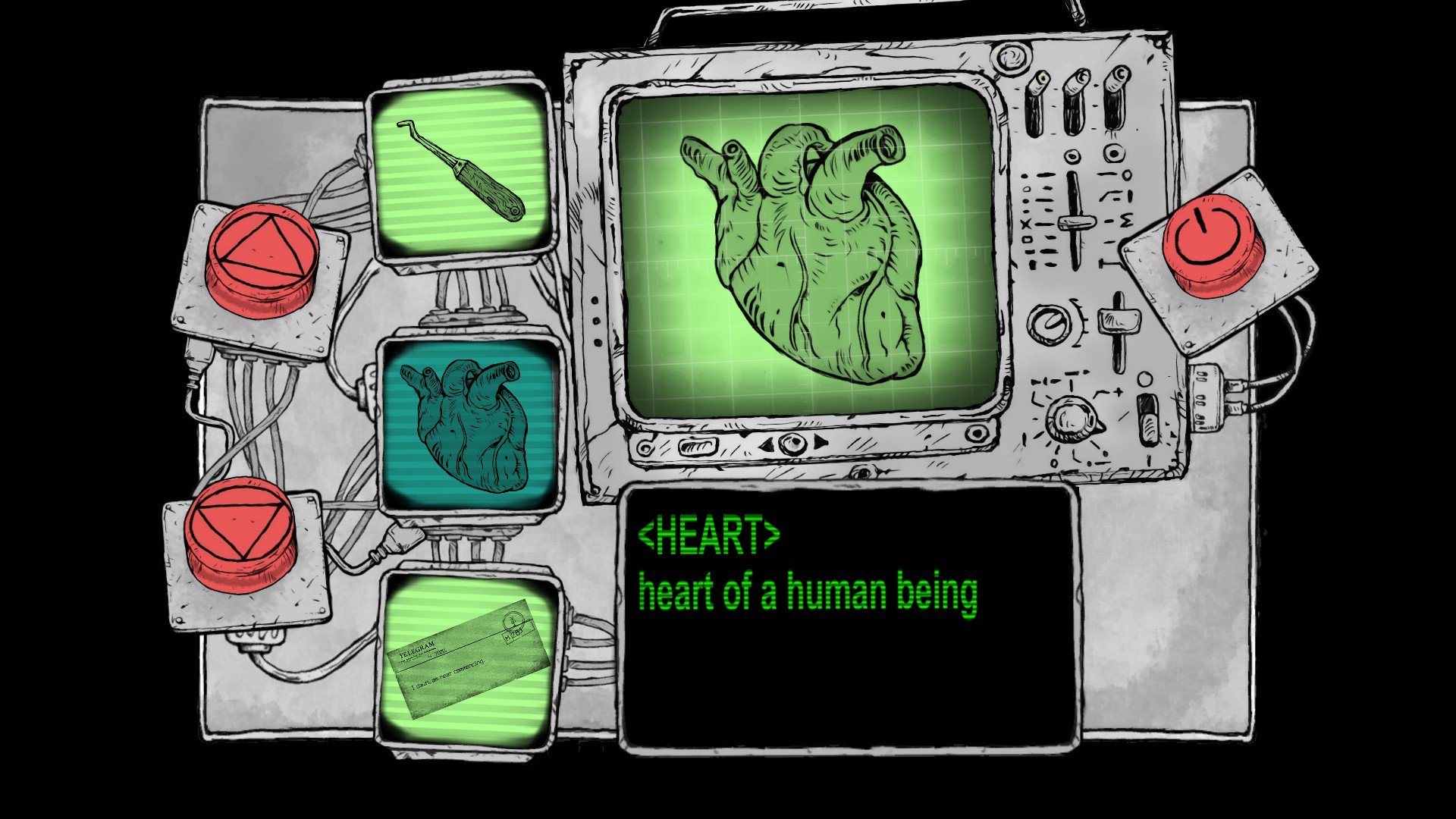

In what will become key pillars of every game moving forward, the sketchbook art style by the hand of Przemysław and otherworldly soundscapes provide an air of mystery and curiosity, an abstracted canvas for you to draw from while still leaving space for you to fill in the blanks. The slow plod of your character conveys a sense of heft to your work, as you move from the very practical electrical repairs of vault 2222 to the more surreal use of a human heart. Paweł's coding work creates a base for a strong, bug free adventure game that feels satisfyingly tactile, with large chunky buttons to press and satisfying bespoke puzzles to solve.

Failure sets up a philosophical setting, a surrealist dream meant for driving the mind to a place of interpretation and understanding. The world feels familiar, with the 80s CRT monitors steeped in green command line text and vaguely post apocalyptic living conditions, but the presence of strange symbols and recordings, links to ancient Greece and more abstract notions such as electricity producing bees and a welding helmet with a giant keyhole on the back are very direct metaphorical inclusions. Consistent threads are laid out from the very first game, with striking imagery connecting these experiences visually and thematically.

And all in good humour, too - it's important to alleviate the heavy thinking with a bit of a laugh sometimes. Even passing through a language filter, the little comments made by the system when trying to use an item somewhere it clearly doesn't fit are always good for a chuckle. I suppose when your family lineage hails from the small village Śmieszkowo - translated as a "funny village" or "a village of laughter" - a bit of brevity allows the heavy thoughts to parse a little easier.

Magnus Imago

Magnus Imago is the first of two static image / hidden object style games, and probably the roughest game to physically play of the quadrilogy. Following in Failure’s footsteps, you will find an eclectic array of items in the environment which then must be inserted in certain places to unlock doors, progress character arcs and generally make it out of this labyrinthine bunker.

The design of the puzzles is the most obtuse, with the interactable objects in the environment often difficult to distinguish from the background itself (the doll head on the stack of potatoes took me way too long to notice). Concessions are made with an “easy” mode, where objects will highlight on hover, however this only partially helps. Thankfully our resident Russian guide PlayZodi has a walkthrough to help.

Despite the highest amount of friction for the series, Imago is more than worth playing through for the visual appeal alone. The sketch work is further enhanced, with splashes of colour seeping into the world, as well as a handful of inexplicable animations to be discovered on and off the beaten path. These sequences resemble the uncanny cutscenes of the PS2 era, most notably the deliberately unsettling and surrealist imagery from the cult classic Drakengard.

These shorts are what Przemysław is referencing in the opening to this piece - animations he had created well before the Magnus games were even an idea, much less a full fledged series. Representations of thoughts and feelings of a younger self, the core of these inextricable expressions carry through current and future works as foundational beliefs to be communicated in the obvious and the abstract. "It's all connected all the time."

Magnus Positive Phototaxis

Magnus Positive Phototaxis takes all the lessons of Imago to build out a much smoother, even more visually engaging hidden object experience, with more explicit imagery and a more focused, chapter based structure. Hover-highlighting is immediately descriptive, with puzzle solutions partially toning down their esoteric nature to follow Failure’s more logical approach.

While religious icons and themes of birth, life and death have been present in the previous 2 entries, Phototaxis begins to coalesce these background elements into a more cohesive package to be pondered on. The marriage between your actions and your experience is at its zenith with this third game, with the balance of abstraction and direct meaning holding that fine line throughout. The surrealist cutscenes (delightfully) also make a return toward each chapter’s end, providing extra nourishment for your brain to chew on as you progress.

Phototaxis feels like a culmination in form and function, possibly the objective best game as a single piece of work of the series. The vibrancy of the artwork and the general flow of the puzzles make for good game design, with the signature art style reaching a climax in grandiosity and perspective. Though it is not the culmination to the series, you start to see the threads between all the games more clearly - a worldview and an intentionality intertwined in a message attempting to be communicated right from the start, while being tweaked and refined throughout the process of growth artistically, personally and professionally.

"You could say [the games were planned to be linked from the beginning], but not precisely specified. Some things came in real time and synchronized. I have it all in my head and in my heart and I want to release it and it's happening in the process, and whether it takes the form of one game or a series of games, it's just the circumstances, I'm open to it. It so happened that it manifested itself in this form."

Lazarus A.D. 2222

For the final game, Lazarus A.D. 2222 is another surprising left turn in design for the series. Item based puzzles and high level abstraction are (initially) replaced with substantial text and dialogue options; a cyberpunk visual novel, containing a sprinkling of mini games and a few branching choices, with a much more literal story for players to grab a hold of.

"We wanted to try to do it a little differently this time. Perhaps [the desire to change approach] also worked subconsciously - there were voices that everything was a bit too blurry, although I like it that way. Stylistically, Magnus Failure was also made differently, so changing the format is not a problem. Basically, it's the same thing, only the form and superstructure have changed a bit."

With Lazarus, you can almost feel a hint of frustration from the creators behind these abstract, thought provoking and at times inscrutable experiences. Sons of Welder have spent the last couple of years trying to get players to think broader than the screen in front of them. These games are all chock full of not just religious iconography, but references to ancient Greece, ponderings on governmental and societal structures, allusions to cycles of rebirth, plenty of musing on our interfacing and reliance on technology, mediations on independent thought and much more.

The whole experience of Lazarus is more direct in its message - most obviously reflected in the game name itself - and is fairly condensed. In some ways it could have used some extra time at the beginning to build up key characters and their existences, but it ultimately gets right to the heart of what the Sons of Welder duo have been gesturing at over the previous 3 games, hitting on the same thematic points with direct text much more than abstracted visual design. That surrealist flair is definitely not gone however - just, different. Until the end, anyway.

The final sequence of Lazarus is best experienced when every other game is fresh in your mind; it’s a culmination of multiple games, a universe of thought and a fitting conclusion to the surreal nature of everything you’ve witnessed up to this point, somewhere in the realms of the infamous episodes 25 and 26 of Neon Genesis Evangelion. In its greatest metaphor for rebirth, this experience may leave you with an urge to re-play previous games to pick up on a little more than you did the first time, or Lazarus itself to see where the other branching paths lead.

"The meaning remains the same - searching for the source. That's how it turned out, that's how I wanted it to be."

A World Created

Both brothers, like many that make games in their off time, have fond memories of getting lost amid strong feelings of wonderment in the digital worlds of yore. Whether these experiences are the the key that unlocks the creative mind or simply a stepping stone on the path is not necessarily the point, but it is certain that the act of play, of massaging your mind with the unfamiliar, fuels our base human desire to build, to grow, to create. It's clear through the Magnus series that these brothers felt that drive, with a need to communicate their own thoughts and vision.

"I have always been doing something creative - drawings, animations, comics, and it was also time for games. I have been dealing with broadly understood graphics for 20 years and I did a lot of it on commission for games. One day, after talking to Paweł (who at that time already had some coding skills), we decided to start making games."

In a lot of ways, the series oscillates between being too unfocused and broad in its approach with having moments of complete clarity and conviction in its message and presentation. The very distinct and deliberate art style throughout the entire collection is what ties this series together so completely; there’s not much like it out there, and is more than likely to pull you through even if you bristle at certain design choices. The multiple shifts in genre help keep every experience fresh, and the growth in both brothers’ skills is readily evident from beginning to end. Sons of Welder’s Magnus oeuvre is best played as a whole; 4 distinct experiences taken as a body of work for you to ingest, interpret, and contemplate.

A World Reborn

Something that this series of games gets at, both textually and through the way each release has evolved and changed, has been that element of growth, of change, of searching for that freedom to seek meaning from creation. Getting locked into patterns creates a sense of entropic degradation; finding ways to become something and learn something new, to be metaphorically reborn, allows us to flourish.

While Lazarus may be the practical conclusion of the Magnus series as it currently sits, there is of course more on the cards for both brothers, albeit in separate projects. Przemysław still has ideas he wants to pursue in the same vein as their more recent works.

"I'm currently working on something new that is very connected to the whole Magnus thing, working name "Amen". I don't know if I will do it with Paweł, because he has his own project now - The Order of the Snake Scale."

I have a high amount of respect for these games. They are short as a positive, where they can be experienced in single sittings while leaving you space to think afterward. They are the types of games that are easy to and are worth replaying multiple times, giving you more room to refine your interpretations. There's enough friction so as to be engaged, but their length alleviates any feelings of being bogged down. They are wildly overlooked and underrated - only a handful of reviews for each. But I am glad the brothers continue to create. The world is all the better for it, and I can't wait to experience what's next.

And for those that are wondering - yes, I did ask. The brothers' father was, in fact, a welder.