Exploring being Good with INDIKA

This piece explores the themes of of INDIKA, thus getting into spoiler territory. If you want to experience it for yourself first, go play it and then read this, however I feel the game stands up as well worth playing whether you already know the full story or not. There’s a lot to notice and think about that this piece does not even touch.

Part way through the opening chapter, young Nun Indika is tasked with trudging through the snow in her habit, collecting water from a well.

You must walk slowly over to the well, lower a bucket into the water by rotating the joystick, bring the bucket back up by rotating in the opposite direction, watch an animation of Indika pour that water into another bucket, walk back over to a barrel about 15 feet away, then watch an animation of her pour that water into a barrel.

You must do this five times.

As you walk back and forth, a narrator waxes poetic about useless labor being key to Christian faith, blind obedience a staple of living a pious life.

Upon finally completing your task, a Sister walks out, mumbles about God and forgiveness, then pours all that water out onto the frozen, muddy ground.

INDIKA, while a game ostensibly about Christianity and faith, is more a philosophical treatise on what it means to be good in a world of both obvious and obscure contradictions. In as much as a 5 hour linear video game built around walking and talking with the occasional puzzle can be, its weaving of basic gameplay systems through the most metaphorical of journeys produces a masterpiece rarely seen in a medium known heavily for shallow bombast and wanton destruction.

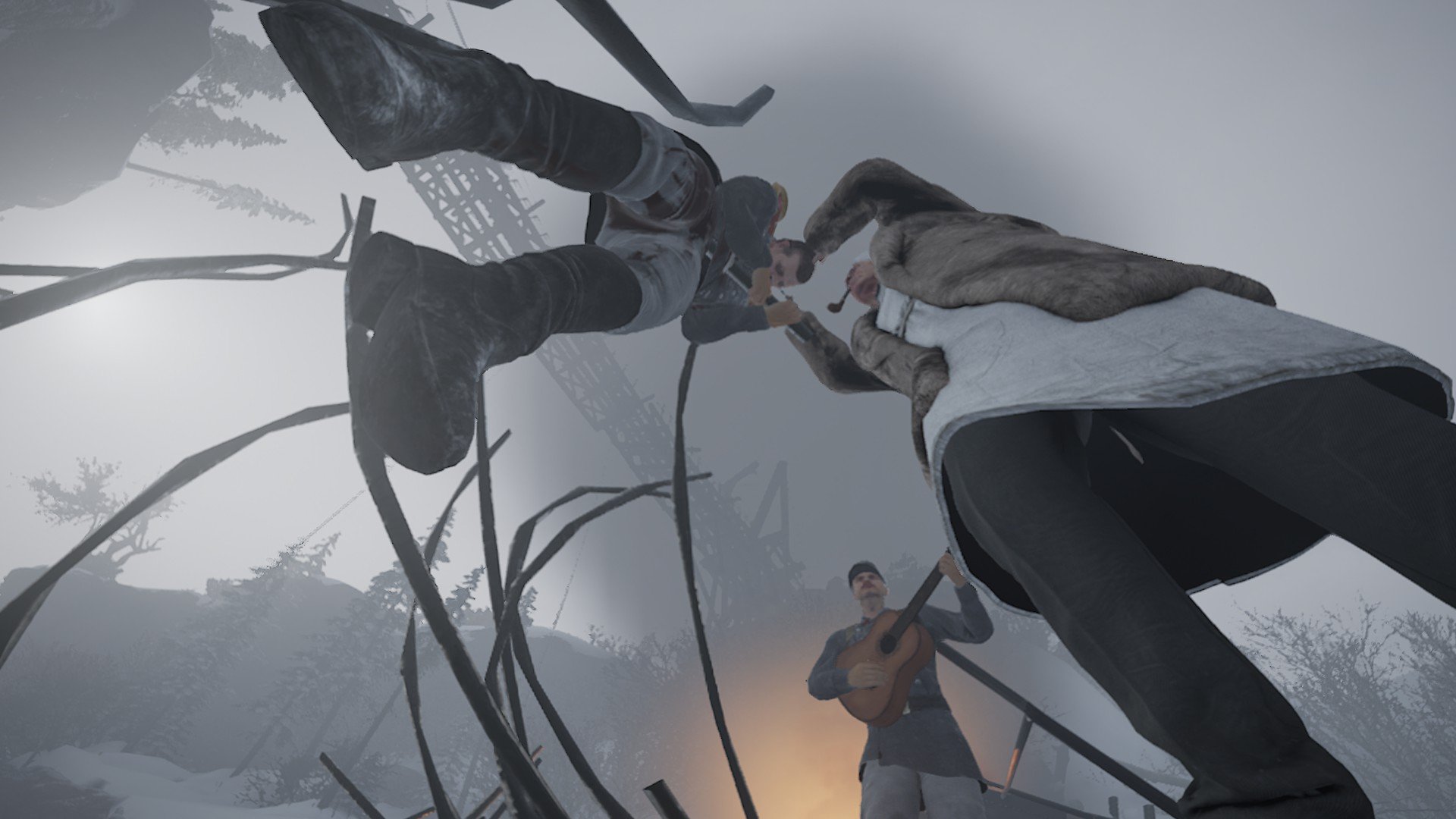

Though immediately oppressive in presentation, with a forlorn protagonist dutifully ready to be guided through a dreary snowed-in convent, INDIKA uses novel fish-eye camera lenses, obscure cinematic angling and an extremely gamey leveling system to throw the player off balance right from the beginning. Walking third-person through the area completing each task set out before you, you gain points here and there, all while an inner voice brilliantly portrayed by Silas Carson narrates Indika's meagre existence. The Devil Inside chastises her with every step, tempting Indika to question; to think.

Very quickly Indika sets out on a journey across old Russia to reach the city church, picking up traveling companion Ilya - an escaped prisoner with a bung arm in search of a miracle - along the way. Broken up into little set piece levels, said journey constantly presents novel locales with increasingly absurd details, should you pay attention to your surroundings for more than a few seconds. Woven through all this are many small humanist parables - some presented as item descriptions, others as discussions between Indika and Ilya (often with her inner voice crudely interjecting).

While Indika's journey appears literal on first blush - you are controlling a human avatar, your motions are very realistic, etc - it's clear from the outset this is a land of metaphor, both subtle and pronounced. A house from the outside may seem regular, yet inside is filled with an uncanny number of wooden dolls set in very human positions. Structures start to have too many levels than makes rational sense, growing larger and more preposterous each step; everything does in fact. If you don't picked up on the strange early, the fish factory and it's tractor tire sized cans ought to smack you right in the face.

During a fireside scene with as much sexual tension the game can muster, Indika comments how nuns are not allowed to remove their habit, even when alone in their rooms at night. As she casts it off and we see her full grace, the double entendre metaphor almost screams at you as you earn an achievement simply titled "Abstinence".

Developers Odd Meter are a studio based out of Kazakstan these days, having fled from Russia not long after the country's invasion of Ukraine began. In interviews, the team discuss their dissonance between despising the actions of their government, while still feeling a very patriotic pride for their country. Russia's culture is built from some all time classical literature, which of course influenced the team. A more thoughtful approach to story weaving, over an "action-packed plot", is clear in their work.

But Why Is INDIKA A Game?

It might be easy to see INDIKA as a story that could easily be told in a film, a play or a novel - hell the stellar animation work alone could easily convert to a feature length picture - but its status an an interactive experience allows for a deeper level of thematic exploration.

The already observed point system initially feels out of place. You began already at level 8, with a point accumulation over certain thresholds awarding level ups to certain skills; "Duty", "Guilt", "Repentance". Leveling these gives you bonuses to allow you to earn more points faster.

Every few chapters, Indika will flash back to her past, portrayed as a little gameplay segment totally incongruous with the rest of the game. Always in nostalgic pixel art, you might play through a kart race, a platforming challenge or a Pac-Man level. During these sessions, you can pick coins up throughout the level in a very classic video game way.

In addition, points are gained throughout the journey mostly by finding collectibles in the world, or by lighting a candle at small shrines to Jesus. That's literal - a giant coin appears out of thin air, classic chiptune sound effect in tow. This is deliberately jarring. Drawing attention to your "piousness" is the point.

The type of Christianity on display here is heavily orthodox, but the base aspect of faith that INDIKA is in conversation with shares aspects among quite a lot - not all, but a lot - of denominations. The common thread is that faith is kind of a scale - if you sin, doing enough good in your life can outweigh this, so you should always try to be good even if you have previously done bad. As far as guides to life go, it's not a bad one to follow - you don't want someone who unintentionally knocked an old lady over at the supermarket to think, "oh well, I'm a bad person, I may as well go on a killing spree now". The idea of "redemption" is meant to be a path to help people do better.

The critique here is focused on the idea that there is a set of rules to follow, specifically around righteousness and punishment, provided by some unknowable deity millennia ago. If someone sins, how do you determine how bad the sin is? Obviously killing someone is worse than, say, opening a letter not meant for you, so there must be some kind of system based hierarchy. So if sin is measured, the good you do must also be.

Early on, you may come across a loading screen hint. "Don't waste time collecting points, they're pointless". It's on the nose, especially when your point score is present in the top right corner of the screen the entire time. How "pious" you are lingers over your shoulder at every turn - even when the game deliberately tells you it's a waste of time. Being a game, you are inherently drawn to collecting more, increasingly your level, becoming "better". What are you going to do, not engage in the game's mechanics?

That's the question though, isn't it. The one thing a video game gives you over literally any other medium, is agency. You make your choices, you control the avatar, you win or lose. You perform actions, which result in consequences. Choose to pick up all the collectibles and gather as many points as you can, or avoid them at all costs to see what happens.

As Indika walks through the fish factory with Ilya, a discussion is sparked between the two about capital-c Choices, such as the ever unanswered parable of free will vs pure chance. As this discussion is going on, you climb ever higher through the mega structure, trudging along catwalks that seem to diverge at points. Where at first it seems like there are multiple paths to follow, there's only ever the one. All other roads very quickly lead to dead ends.

At the culmination of the fish factory, Indika has to make a choice. Does she go against Ilya's direct wishes, breaking his faith, or does she do what she can clearly see is the logical course of action that needs to be taken? Afterward, as she rides elevator like contraptions up to a balcony while she questions her decision, she is presented with two doors. Entering one, she very quickly finds that both lead to the same place.

The game ends with a very explicit message, with the heaviest metaphor it could possibly convey. The surrealism comes to a head in a way that, I think at least, it pulls off perfectly. Indika performs actions that are blasphemous, and loses all points / levels as a result. No matter how good you were, those actions ultimately meant nothing. That is until Indika gets her hands on a holy trinket that produces as many points as you want - infinitely. There is no threshold that is “good enough”. Nothing changes.

The final action you take is to have Indika throw away the trinket and embrace now. Be freed from your internal conflict - go make your own choices. The points will not save you. Only you can do that.

Plenty online take issue with this approach. However, though it is a critique of the idea of faith, this game is one of philosophy, with religion being the lens to view that through. Are you a good person because you blindly followed some rules you were told to follow, or do you make your own choices when doing what is right blatantly disregards said rules? This story is not meant to be tidy and clean. It’s crunchy and thoughtful, messy and human. It’s not a frictionless meal to slurp down and forget - it’s a question, waiting for you to ask.

Agree with me or don't, play the game or ignore it; one way or another, this is your life to live. Only you can make the choice on how to live it.

Code for INDIKA on Steam was provided for the purposes of this piece.